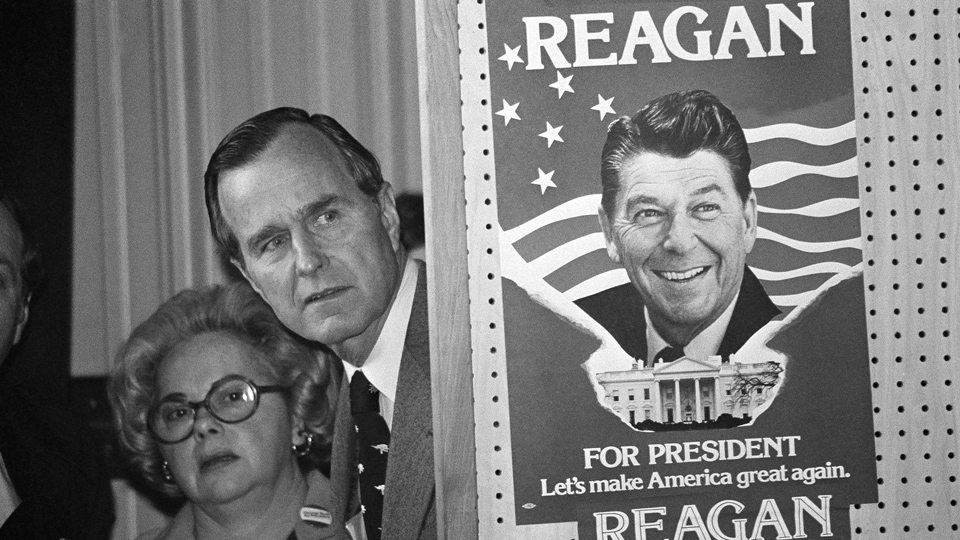

George Bush espera detrás de una mampara adornada con un cartel de uno de sus rivales, Ronald Reagan, con el lema "Hagamos América grande otra vez" antes de saltar al escenario en un evento republicano en Columbia, Carolina del Sur, el 4 de marzo de 1980. (AP)

George Bush espera detrás de una mampara adornada con un cartel de uno de sus rivales, Ronald Reagan, con el lema "Hagamos América grande otra vez" antes de saltar al escenario en un evento republicano en Columbia, Carolina del Sur, el 4 de marzo de 1980. (AP)En 1980, Ronald Reagan ganó la mitad de los votos en la primaria de New Hampshire en un pelotón de siete candidatos republicanos, doblando el total de votos recibidos por su más inmediato perseguidor, George H.W. Bush. En las dos semanas que siguieron, el ex gobernador de California sumó victorias en cinco de las seis primarias que se celebraron, lo que le sirvió para confirmar que podía competir con Bush y John Anderson en Nueva Inglaterra y destrozar a Bush y a John -Big John- Connally en Carolina del Sur y el Super Martes sureño (Alabama, Georgia y Florida); pero, sobre todo, para hacer desistir a Gerald Ford de su propósito de reclamar la nominación más adelante. Craig Shirley nos relata aquellos trece días en su libro Rendezvous with Destiny:

Now the “manly” Reagan was surging. George Bush's decision to redouble his efforts in Massachusetts and Vermont seemed not just prudent but critical by this point. A new Boston Globe poll released just four days before the primaries showed that Bush's once-massive lead in the Bay State had all but disappeared: Reagan and Bush were essentially tied, at 33 and 36 percent, respectively. John Anderson's strategy was paying off, as he scored an impressive 17 percent. Only Howard Baker fared poorly, polling at just 6 percent. The race had gotten so tight that the candidates shuttled for a week between the two New England states by car and plane. Except for Reagan, that is: He adhered to the previous plan of spending only one day in Massachusetts. Most of his effort would go into a mailing to 270,000 of the state's Republicans.

Bush was doing his best in Massachusetts to push Reagan into a right-wing corner and Anderson into a left-wing corner so he could seize the middle for himself. The primary, he said, would, “sort out the fringe candidates.”

The stunning breakdown in New Hampshire called for a radical change in Bush's message. Bush's adman, Bobby Goodman, huddled with Jim Baker, Dave Keene, and their candidate. They decided that they could not keep dancing around the age issue. The most effective way to attack Reagan's age, they concluded, was to create commercials featuring senior citizens speculating that Reagan couldn't have the necessary vitality anymore because they didn't have it anymore. “Onerous geriatric judgments” was how Evans and Novak put it.

Bush began telling Republicans that “a vote for Anderson is a vote for Reagan.” Anderson didn't much like being called anybody's cat's-paw. He crisscrossed the state, and pledged to keep campaigning until he ran out of clean laundry. Anderson told voters, “There is something different about me,” or, speaking in the third person, “There is something different about John Anderson.” His speeches were liberally sprinkled with the words “I” and “my.”

Bush, more than gun-shy after the Nashua experience, ran away from a proposal to debate Howard Baker in Vermont, screaming “ambush.” Baker wryly took stock of Bush's response and said, “George must have suffered more from New Hampshire than I thought.”

Adding to the Bush team's aggravation was the fact that the mudslinging was intensifying with John Connally in South Carolina. Connally had accused the Bush campaign of “dirty tricks,” charging that a black supporter of Bush's was spreading “‘walking-around’ money” throughout the state. The charge was scurrilous, but Connally soon became embroiled in his own controversy. Bush backer Harry Dent—who loathed Connally almost as much as he despised Reagan—accused Connally of attempting to buy the black vote. Dent would not let the issue go, and the fight between the two campaigns turned ugly. John Connally III, acting as his father's newest campaign manager, called Bush “reprehensible.” A Bush spokesman fired back, using a polysyllabic obscenity, and called young Connally's charges “a lie.” Bush's aides fretted that their campaign was wasting time going after the wrong man, but Reagan couldn't have been happier. The more time the two Texans spent banging on each other, the less time they had to go after him. He could stay above the fray.

Connally was fighting hard in South Carolina, but he was not connecting with voters as one might have expected for a man who had plowed fields in Texas as a barefoot boy. At one stop in Greenville, Newsweek reported, he “declaimed on the virtues of revisited depreciation schedules as a means to promote capital formation.” The crowd of working poor had no idea what he was talking about.

(...) GERALD FORD FINALLY CAME out from merely shadowboxing with Reagan and threw a big left hook at the Gipper. In an interview with his old friend Barbara Walters of ABC he said there was a “50–50” chance that he would get into the contest. Ford denied to Walters that he would get in to “stop one candidate.” But soon, in an exclusive interview with Adam Clymer of the New York Times, Ford made his target clear: “Every place I go and everything I hear, there is the growing, growing sentiment that Governor Reagan cannot win the election.” He made the inevitable comparison to Barry Goldwater's crushing loss in 1964. When conservatives in the GOP responded with outrage, Ford backtracked, saying his comments had been taken out of context. “I said that there was a perception he was too conservative,” Ford claimed, not too convincingly.

Reagan counterpunched, reminding reporters that he'd been twice elected governor of a state with a 2–1 Democratic registration edge—and that he'd beaten Ford in the 1976 southern primaries with the help of Democratic voters. Reagan challenged Ford's noncandidacy, saying he should “come out here.… There's plenty of room.”

Ford's posturing did nothing to help George Bush. Bush had already been accused of being a “stalking horse” for Ford, and if Ford got in the race, he would divide the anti-Reagan vote even more. Ford supporters placed the former president's name on the ballot in relatively liberal Maryland. In Illinois, thirty-five former supporters of Howard Baker announced their intention to run as Ford delegates. Bush's team now had something else to worry about. Bush said that he was not going to “roll over” for Ford, while Dave Keene said Ford was “mistaking affection for political support.”

Ford's narrow loss four years earlier to Carter ate at him more than he let on. He wanted another shot at Carter, and felt Reagan owed him that shot. Years later, journalist Tom DeFrank wrote that Ford “emphatically told me … that Reagan should have graciously stepped aside in 1980 so he could run against Jimmy Carter again and was monumentally irked when he didn't.”

While Ford was blasting Reagan, another former Republican standard bearer finally endorsed the Gipper for president. Barry Goldwater had supported Richard Nixon over Reagan in 1968 and Ford over Reagan in 1976. Reagan's famous speech in 1964 had raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for Goldwater, but it took sixteen long years for “Mr. Conservative” to return the favor.

Reagan had not yet consolidated the “New Right” behind his drive for the White House. More militant members had been withholding their support for various reasons while others had cast their lot with Phil Crane or Connally. The first to support Reagan was the Fund for a Conservative Majority, whose pro-Reagan independent expenditure effort had begun in New Hampshire and carried through all the primaries, including Illinois. The second to come on board was Christian Voice, which launched an ambitious effort to contact five million Christian voters urging them to support Reagan and contribute to their organization. The funds were then used to put a half-hour interview with Reagan on independent television stations, including Christian stations in the South and Midwest, according to Gary Jarmin, head of the organization's Washington office. With Reagan speaking about his faith and moral stands, Christian Voice believed that this effort could mobilize millions of “moral” voters—born-again Protestants and conservative Catholics, Jews, and Mormons—in support of the Gipper.

Another organization of the New Right, Americans for Conservative Action, blanketed South Carolina with anti-Bush flyers, charging him with being for gun control and federal funding of abortion. Bush was livid and was forced to defend himself yet again against spurious charges.

The millions of dollars in independent support came none too soon for Reagan. Bill Casey had slashed campaign costs across the board. In South Carolina, for example, Casey canceled Reagan's charter plane, a Boeing 727, and instead rented a bus with “Reagan Express” signs taped on the side. The move saved tens of thousands of dollars, but it also created mayhem with the traveling press, some of whom were left high and dry, forced to hurriedly schedule commercial flights to cover Reagan's speeches. The decision to curtail the charters did not make for a happy press corps, but Reagan was in high spirits, out and about, meeting voters, listening to them, talking to them. He sat with a reporter from The State, Mike Clements, and mused about missing his ranch and the beautiful South Carolina countryside. After a grueling day, Reagan was still fresh as a daisy, while the staff and the reporters on the bus were dragging. Reagan explained, “You draw strength from the people.” Reporters were now noting how good Reagan looked, how ruddy and healthy and vibrant he seemed.

Riding on the bus with Reagan was the great former Yankee second baseman Bobby Richardson, but the biggest treat for Reagan came when he was introduced to a baby born just a month earlier on February 6, his birthday. The infant was named “Reagan.” The child would be the first of many to bear that honorific.

ON MARCH 4, GOP primary voters went to the polls in Vermont and Massachusetts. The day before the primaries, Bush was asked how he felt. The man who had been the front-runner just a week earlier replied, “Nervioso, muy nervioso.”

He was right to be nervous. His formerly massive lead in Massachusetts had practically vanished. Bush barely eked out the victory. He received 31 percent of the vote … but so did John Anderson; Bush edged Anderson by only 1,200 votes (124,316 to 123,080). And Reagan nearly matched them both; despite having done little campaigning there, he tallied 29 percent (115,125 votes). In Vermont, Bush came in a disappointing third with just 23 percent; Reagan came in first with 31 percent, while Anderson claimed 30 percent.

The big winner of the day—though he won neither primary—was Anderson. After nearly stealing both primaries, he got the lion's share of laudatory media coverage, including an appearance on the Today show. Lots of independents and liberals had crossed over to vote for Anderson, which might have explained why he happily flashed the peace sign for photographers.

Moreover, a major constituency of Anderson's was young students, and New England was chock-full of them, especially Boston, where one in twelve inhabitants was enrolled in college. On primary night Anderson's young troops, students from Harvard, Tufts, Boston University, and dozens of other universities, gathered at his headquarters, drank beer, and screamed each time a network anchor gave out more favorable news about their man's progress. Anderson had attended Harvard Law, so he understood the culture of the campus. Bush referred to Anderson's showings as a “freak” occurrence, and with that, when Anderson appeared on campuses, he addressed his young supporters as “my fellow Anderson freaks.”

Reagan was scored a survivor for having won two in the Northeast and been competitive in a third. But columnists pummeled poor Bush. He was only one delegate behind Reagan, 37–36, but expectations had once again defeated him. He had been expected to score a major win in the Bay State instead of a narrow win and to place first or second in Vermont, not an unimpressive third. The Miami Herald called it a “minuscule boomlet” and Bush himself candidly said, “A landslide it wasn't.”

Moderates, growing more concerned about Reagan in Connecticut and other states around the country, began sending Ford telegrams of encouragement. It would be a major embarrassment for Bush to lose in the state where he had grown up.

(...) AFTER HIS DISAPPOINTMENT IN New England, Bush pressed on to Florida. He took it to Reagan, reminding the GOP faithful that when they had nominated Goldwater in 1964, “the party self-destructed.”

Bush's campaign had produced some tough radio and newspaper ads going after Reagan, but then scrapped them at the last minute for fear of a backlash. The ads accused Reagan of “flip-flops” over the ERA and abortion. Then they made a harsh comparison between Carter and Reagan: “Can we afford the same mistake twice?” In a final blow, the ads said Reagan “has no real understanding of the dangers we face in the decade of the '80s.… He didn't even know who the president of France was”—a reference to an interview Reagan had done with Tom Brokaw of the Today show several months earlier. Dave Keene had told reporters several days earlier that Bush's campaign would pursue a tougher line of attack on Reagan.

Although Bush was drawing big crowds throughout Florida, the volatility of the GOP contest fueled speculation that former president Ford might—or should—get into the race. Campaign maestro Stu Spencer made several probing calls around the country to Republicans, taking soundings as to how they felt about Ford jumping in. Since the calls were self-selected, naturally the vast majority were a go for Ford. Spencer was a laid-back GOP operative who had been active in grassroots politics until he ran Nelson Rockefeller's California primary campaign that ultimately lost to Goldwater in 1964. Reagan had picked Spencer and his partner, Bill Roberts, to run his winning gubernatorial campaigns in 1966 and 1970. But Spencer had been excluded from the early planning for Reagan's 1976 insurgent challenge, so he worked instead for his fellow moderate Ford. He complained privately that Reagan was too conservative to be president. He also groused that Ed Meese and others had cost him business in California, and this too prompted his desire to stop Reagan.

Ford went down to Florida to give a speech at Eckerd College in St. Petersburg—for which he was paid $50,000, as with all of his appearances. The three networks, the BBC, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and dozens of other outlets caught up with Ford at the small college to read the tea leaves. The national media were on their guard. The past three years they had heard “Ford is running,” “Ford isn't running,” “Ford might run”; they referred to him behind his back as the “Hamlet of Rancho Mirage.”

Spencer coyly told the reporters, “I think you can look for a news story next week.” An undergraduate who attended Ford's lecture on “National Character” was skeptical. “I've never heard anybody who can talk for an hour and not say anything,” said Tim Storm.

If Ford was going to take the plunge, he would have to decide quickly. Filing deadlines were looming in many states, fundraising was imperative, and there was the matter of staffing such an operation. Not to mention bank accounts, phones, stationery, office equipment, scheduling, babysitting the media, chartering a plane, food, coffee, liquor. It was akin to building a major corporation over a weekend.

Ford aides began drawing a campaign plan. In early March, a group led by Thomas C. Reed, Ford's former secretary of the air force, and Leonard Firestone, Ford's wealthy next-door neighbor in California, formally created the Draft Ford Committee. Reed, like Spencer, had once worked for Reagan. A young former Ford White House aide, Larry Speakes, was recruited as the committee's spokesman. Also working on the Ford campaign plan was none other than the Bush campaign's pollster, Bob Teeter. People were gossiping about that one, but one source later said that Teeter had only done so with Jim Baker's approval.

Everyone in Ford's inner circle was convinced that the former president was running. Ford had already met once in secret with John Sears, and he scheduled a second, more public meeting with Sears to discuss his campaign. After the meeting, Sears and Ford held a press conference. Sears told the gathered media, “I believe Ford could be nominated. I don't think the timing is too late.” Sears was asked whether he thought Reagan was unelectable, but refused to answer.

More encouragement for Ford came from moderates in the GOP. Bob Dole, still not out of the race formally but out of the race in every measurable way, called Ford and urged him to jump in. Any way Dole could, he would twist the knife into his old enemy Bush. Republican governors Robert Ray of Iowa, William Milliken of Michigan, and Richard Snelling of Vermont came out for Ford as well.

Finally, Henry Kissinger came out publicly and called on Ford to jump into the GOP contest. Kissinger had met with Ford for more than two hours at Rancho Mirage and emerged saying Ford had a “duty” to run. Of all Ford's men, Kissinger may have been the most ideologically opposed to Reagan's election, as it would mean a repudiation of détente. He'd said for months that the only candidate running whom he could not work with was Reagan.

Kissinger told the press that Ford was the only Republican of stature in whom foreign leaders had confidence. But he disavowed any knowledge of such earthly matters; the master Machiavellian infighter and political operator told reporters with a straight face, “I am not a politician.” Reporters giggled and smirked. It was nearly as disingenuous as Ford telling reporters that he was not “scheming and conniving” to get the nomination. Newsweek reported that the former president would reappoint Kissinger secretary of state if he once again occupied the Oval Office. Kissinger coveted a path back to power.

Ford went to New York City and met with a dozen prominent Republicans, all Reagan critics, all of whom encouraged him to run, including Senator Jacob Javits. They came away convinced that Ford would indeed make the race. Grass-roots efforts to file slates of Ford delegates in New York, Connecticut, and Michigan were moving forward.

ABC's World News Tonight, anchored by Max Robinson, opened dramatically on March 7 with a report that “former President Ford, who four years ago went to the political mat with Ronald Reagan and won, is apparently very close to getting into this year's contest to try and head Reagan off once again.”

Evans and Novak reported that Ford had made the decision to get in once and for all. He would become a formal candidate on March 20. That was it. The two columnists had the best sources in journalism, even though some critics referred to them as “Errors and No Facts.” Rowland Evans had spoken directly to Ford, who had expressed his concerns that the primary season had not produced a consensus candidate and said that he figured he could garner the entire Bush and Anderson vote while cutting into Reagan's base.

Howard Baker by this point had finally dropped out of the race after repeated weak performances, and two of his now unemployed aides, Doug Bailey and John Deardourff, told reporters they were signing on to the Ford campaign. Lowell Weicker endorsed the Ford candidacy, but most in the GOP viewed this as a mixed blessing at best.

In mid-March, Bob Mosbacher, a Bush confidant and fundraiser who nonetheless worshiped Ford, went into Dave Keene's office at Bush's headquarters. Mosbacher shut the door and said to Bush's political director, “While we have done a great job thus far, it is clear that only the president [Ford] is in a position to stop Reagan and that we must therefore figure out how to get Bush to step aside so that Ford can be convinced to enter the race.” Keene was livid. As he recalled years later, “I told Mosbacher the idea was absurd, and if he thought there was a chance in hell that I'd participate in such a scheme or support Ford over Reagan, he was nuts.” Keene, who had a temper like few men in politics, didn't stop there. His voice rising, he told Bush's fair-weather friend, “There are few times in life when one can say he made a real difference, but I could always look back on '76 and the fact that I'd played a role in ridding the nation and the GOP of Ford.” Keene followed with a string of obscenities about Ford and Bush's betrayer sitting there in front of him. Mosbacher left Keene's office and they never spoke again.

Keene later reflected, “The Bush campaign consisted of those who really thought Bush would make a good president and were supporting him for that reason; those who thought he'd make a stronger general election candidate than Reagan; and those who were simply using him because they hated and/or feared Reagan. Bush sometimes couldn't tell these folks apart.”

All the Republican candidates were forced to address the growing Ford rumors. Bush said Ford's entry would “complicate” things for him, but he kept telling people he didn't think Ford would get into the race. Anderson got off a good line when he said Ford should not “disturb his retirement.” Reagan kept his cool and showed off his wit. When reporters asked why Ford might be willing to give up the golf links for the campaign trail, Reagan quipped, “Maybe he's developed a slice.” Reporters laughed.

The next day, though, Reagan toughened up his message. “Frankly, I thought it was very thoughtless of him to say anything that could give comfort and aid to the enemy,” referring to Ford's comments that Reagan could not win.

Within a matter of hours, word leaked that it was official: Ford would get into the race the following week.

Ford went through a charade with the media, proclaiming that he was playing no role in the draft-Ford campaign. In fact, behind the scenes, he was taking and making phone calls and lining up support for his imminent entry.

Reagan, however, was holding all the cards and he knew it. If Ford got in, it would doom Bush and Anderson, especially with the southern primaries coming up. They would divide the moderate GOP vote, leaving the conservatives for him. Asked whether he thought he could beat Ford, Reagan smiled and said, “Yep.” When pressed as to whether Ford would tarnish his own image by joining the race, Reagan quipped, “It's a nice thing to think about.” Reagan was practically begging Ford to run.

RONALD REAGAN WAS IN Florida on the day of the South Carolina primary, but he still mangled both Bush and Connally in the Gamecock State. With help from his in-state organizer, an intense young man named Lee Atwater, Reagan took 54 percent of the GOP vote while Connally received 30 percent and Bush a paltry 15 percent. Reagan, helped by crossover Democrats, swept all six congressional districts and, with them, all twenty-five delegates.

Democrats voting for Reagan did so at their peril. The state Democratic Party chairman, Donald Fowler, warned that they might not be allowed to vote in his party's caucuses the following week. Conservative Democrats in the state found Fowler repugnant. Turnout was five times as high as the record previously set in 1974. A furious Fowler threatened that he would force Democrats to sign a pledge of fidelity, but loyalty oaths had been out of fashion in the South since Reconstruction.

If there had been a vote-buying scheme cooked up by either Bush or Connally, it had not produced. In one all-black precinct in Columbia, by 5 P.M. only two voters had shown up to vote in the GOP primary.

Connally failed even in his modest goal of keeping Reagan under 40 percent. He'd spent $500,000 out of his own pocket in South Carolina, but it was for naught. Big John put what was left of his campaign on hold and went home to Texas to “reassess.” He finally faced reality and referred to Reagan as “the champ.” Connally had been helped by one of the more creative media consultants, Roger Ailes, but even Ailes's powers could not stop the runaway train of Ronald Reagan. After thirteen months and millions spent, John Bowden Connally had nothing to show for his efforts save one lonely sixty-seven-year-old delegate from Arkansas, Ada Mills. She became known as the “$11 million delegate.” Toward the end of the road, Connally—who was all personal ambition—told a reporter, “I'm not consumed by personal ambition.”

Reporters mourned the demise of Connally. From his Stetson right down to his silver inlaid cowboy boots, he was always entertaining, always good copy, he always had a good joke, and he was a terrific public speaker.

Prior to his withdrawal, Connally called Reagan to inform him of his decision. Reagan listened but wisely did not ask for his endorsement; instinctively, he knew this would not have been the proper time. There was no report of Connally's calling Bush.

In the end, there was just too much of Connally for voters to swallow: too much Texan, too much wheeler-dealer, too much rumor and scandal and bravado. His campaign also spent foolishly, including furnishing and renting a lavish apartment in Virginia for his campaign treasurer. They had chartered expensive planes and expensive hotel rooms. His first manager, Eddie Mahe, was paid almost $9,000 a month. Of the $12 million Connally spent, about $10 million went to operations, staff, and consultants. Only about $2 million went into media. But there was another reason why Connally never took off:

“What did us in?” lamented Connally's longtime aide Julian Read. “His name is Ronald Reagan. And he's been on the road and on television for years. He has a very solid, emotional constituency that we didn't penetrate. He just beat us.” Losing consultants never blame themselves and losing candidates never blame themselves.

George Bush's foolish diversion into South Carolina—a decision motivated by his contempt of Connally—hurt his campaign badly. The original plan had been to bypass the state and let Reagan and Connally beat the tar out of each other and deplete their resources. Bush could then take on either a weakened Reagan or a resurgent Connally. Bush had unwisely gambled time, money, and people in an attempt to achieve an impossible win. The two Texans made the classic mistake of getting into an ugly spraying match with each other; GOP voters, repulsed by the brawl, went with Reagan.

Reagan might have won South Carolina in any event, but the fight between Bush and Connally—with the Bush campaign producing seedy tape recordings of conversations between Connally's in-state and Washington staffers plotting a scheme to “buy” African-American votes in the state—pushed Reagan well over the 40 percent his campaign thought he'd get. Reagan smilingly called himself “cautiously ecstatic.”

BEFORE THE SOUTH CAROLINA primary, Bush had been competitive with Reagan in Alabama, behind just 45–39 percent, according to a Darden poll. He was shelling out several hundred thousand dollars, mailing the state heavily, and spending considerable time there. With Connally effectively out of the contest, Bush might have expected to reap some of the 10 percent support of his old antagonist. But when the ballots were counted on March 11, he was demolished in Alabama. Reagan, who had spent just a little over $30,000, took every county and received almost 69 percent of the GOP primary vote to Bush's 26 percent.

In Georgia the same day, Reagan did even better, winning 73 percent to Bush's paltry 13 percent. And in Florida, Reagan received more than 57 percent of the vote and Bush 30 percent. On the day, Reagan took 105 delegates to only 9 for Bush. It was especially embarrassing for Keene, who had billed himself in part as the Bush campaign's ace in the hole for the South.

Alabama and Georgia allowed crossover voting, and conservative Democrats helped add to Reagan's handsome victories in each. Florida had a closed primary and Reagan still won handily there, which should have been a wakeup call to those who said Reagan was not the favorite within the GOP. When Reagan won in crossover states, critics complained that Democrats should not be allowed to decide the nominee of the Republican Party. But in the same breath they said Reagan had no appeal beyond the conservatives in the GOP.

Reagan should have won Florida in 1976 and would have had he not unexpectedly lost New Hampshire to Ford and then stumbled on the Social Security issue in the Sunshine State. Reagan wasn't about to make the same mistake twice. This time he made it clear to the oldsters that the government-run pension plan would stay healthy if he was elected.

Reagan had also gone hard after the Cuban-American vote in Florida. He charged that Carter had “eliminated a clandestine radio station that was broadcasting messages of freedom to Cuba.” He said “there was ‘excessive surveillance’ of anti-Castro refugees, and Cubans frequently were hauled up before grand juries.” Reagan laid a wreath at a memorial for the Cubans who had died in the Bay of Pigs invasion. Everywhere he went he was greeted with “Viva Reagan!” by the enthusiastic anti-Communists. He shucked his coat in the sweltering heat and told the crowd in Little Havana, “Our country still has an obligation.” Someone yelled out, “We are ready again, anytime.” He then plunged into the gathering of thousands.

Bush limped back North after being bloodied in the southern primaries. But he was an extremely competitive man and turned away talk in his campaign to pack it in and call it a day. The good news was that Bush had beaten Reagan in Iowa, Maine, Puerto Rico, and Massachusetts; he still had money in the bank and more favorable terrain ahead in Illinois, New York, Connecticut, and Pennsylvania; he'd outlasted Bob Dole, Howard Baker, and John Connally; and he had become quite able on the stump, firing up crowds when he was moved to do so. The bad news was the specter of Gerald Ford getting in. In desperation, Bush suggested that Ford's age could be used against him, as it had been used against Reagan.

Bush was distraught that he never had the chance for a two-man race with Reagan. Just when it appeared he might finally get his wish, John Anderson had appeared out of nowhere. Each vote Anderson was taking was coming right out of Bush's back pocket, it seemed to Bush's advisers. In the weeks up to and after Iowa, Bush had become the media darling. After the New England primaries, the white-haired, bespectacled Anderson stirred the passions of the national media. Reagan had the conservatives, Anderson had the media, and Bush was left holding air. Bush's press secretary, Pete Teeley, said Anderson was getting “the kind of influx of publicity, money, enthusiasm and support that we had after Iowa.”

Anderson had bypassed the southern GOP primaries, knowing his message would not go down well there. He was waiting for the chance to take on Reagan and a weakened Bush in the March 18 primary in Illinois, his home state. He also was making plans for Wisconsin's upcoming primary, counting on the state's progressive Republican tradition. Anderson was clearly courting liberals; he took out a full-page ad in the New York Times with an open appeal to its liberal readers for campaign contributions. The title of the ad was “Why Not the Best?” No one seemed to remember that this was the title of Carter's campaign book in 1976. The ad was plastered with kind comments from the Beautiful People, including writers Sally Quinn of Georgetown and Tom Wicker of Manhattan. It also came to light that Anderson had signed a direct-mail fundraising letter for the National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), which planned to give the money to George McGovern, Morris Udall, and other pro-choice representatives.

(...) A NEW ABC NEWS–HARRIS poll showed Ford to be favored over Reagan among Republicans, 36–32 percent. With independents thrown into the mix, Ford widened his lead over Reagan to 33–27 percent.

Tom Reed of the Draft Ford Committee held a press conference in Washington and released the names of one hundred prominent moderate Republicans who supported Ford's entry into the race. Reed's scenario for Ford to win the nomination, however, stretched credulity. His plan was for a Ford surrogate to run in Ford's stead in Texas, since the filing deadline had closed there, and then beat Reagan in the Lone Star State. In addition, Ford would have to beat Reagan in California. Reagan had beaten—or more accurately, crushed—the incumbent Ford in both states in 1976.

Before sweeping the South, Reagan had wanted Ford to get in and divide the moderate vote. Now, with the momentum on his side, Reagan wanted Ford to stay out. Not because the former president might gain the nomination—there was little chance Ford could do this unless there was a brokered convention—but because a Ford entry into the race might marginalize Reagan. Nelson Rockefeller's late entry in 1964 had marginalized Barry Goldwater, preventing him from reaching out to middle-of-the-road voters in the general election.

Ford continued to draw extensive media attention. He leveled Jimmy Carter, saying, “My sole, single purpose … is to get President Carter out of the White House.” Ford didn't stop there, telling a Republican audience, “The nation is in peril. Mr. Carter has forfeited his immunity at home. This country is in deep, deep trouble.”

Ford's attack was harsh, especially since he'd met with Carter that very morning and come out of it praising the president. But that was Washington. Kiss 'em in private and bash 'em in public. A Carter man returned the Ford fire: “He's going to get chewed up alive if he comes in. He's a nice man, but let's face it, his were do-nothing years.”

In his Washington Post column, David Broder pointed out the practical impediments to a Ford candidacy. Ford would miss filing in twenty-one primaries that would choose 908 delegates out of 1,994. Also, Ford's charge that conservatives could not win a general election drove men and women on the right up the wall. They'd had it thrown in their faces ever since the days of Goldwater and Bob Taft, and if Ford got in and actually stopped Reagan, the party would be split so badly that it might never be repaired.

Broder was one of the two or three best political reporters of the era. Soft-spoken, mannerly, but with a drive for the facts and boundless energy that few could match, he wrote long, thoughtful pieces that were considered “must-reads” in Washington. Even as Carter was sweeping away the Kennedy challenge and looking to stomp Reagan, Broder wrote a long piece in early 1980 about how Carter could be more vulnerable to Reagan than anyone realized.

POSTMORTEMS ON THE SOUTH were all good for Reagan, mostly good for Carter, and awful for both Kennedy and Bush. Carter was now ahead of Kennedy in the delegate count, 283–145. Reagan had opened up a delegate lead over Bush, 167–45.

The presidential combatants descended upon Illinois, where new polls had Anderson surging into first place, Bush faltering, and Reagan moving into second place. It was the first midwestern primary and would also be a key battleground in the fall election.

All waited with bated breath for Ford's decision. Ford privately lamented that he was not getting the outpouring of support from around the country that he'd hoped for. He expressed a twinge of bitterness that few of the GOP officials he'd campaigned for had come out for his candidacy, especially key moderate governors Lamar Alexander of Tennessee, Dick Thornburgh of Pennsylvania, and John Dalton of Virginia.

In a meeting with reporters over breakfast, Ford was clearly having second thoughts. “Reagan has the strongest base of support I've seen in politics,” he said.

Two days later, Ford held a subdued press conference outside his home in California with wife Betty at his side and declared, once and for all, that he would not run in 1980. Her recent victory over addictions to alcohol and pills was a factor in his decision, but his supporters were crestfallen. Only twenty-four hours earlier, they had been happily preparing to relaunch the USS Ford. Now it was “final and certain” that he would not run. Ford declined to endorse any candidate, but made it clear he intended on making it his business to defeat Carter in the fall. He choked up a bit during his remarks.

Ford came to his decision after one final meeting with his supporters who reviewed his bleak chances. Among those attending the two-hour meeting were Congressman Dick Cheney; Alan Greenspan, a former White House economic adviser; Doug Bailey, the former Baker media man; Tom Reed; and Stu Spencer. Grassroots Republicans were sharply divided over Ford. A Gallup poll showed that while 49 percent said he should get in, 46 percent said he should not. The most important poll, of his family, had his wife and three of his four children against his making the race.

Above all, the decision was about the numbers—the numbers on the calendar, the numbers of missing supporters, and the numbers of dollars he'd have to raise. If Ford believed he had a reasonable chance, he would have gotten in. He loved being president. But Reagan was piling up delegates and Ford would be competing with Bush and Anderson for the remaining moderate vote.

The Ford boomlet ended with a whimper. Larry Speakes, at the headquarters for the Draft Ford Committee, said, “About all we have is a phone bill to pay.” With that, Ford's thirteen-day campaign folded its tent.

Bueno pues se fueron tres de una tajada. Yang, Bennet y Patrick se retiran. Entre los tres el porcentaje a repartir es casi simbólico.Después de Nevada veremos si no hay más. Por cierto Sanders parece fuerte en Nevada. Si gana en ese estado de fuerte influencia latina ya se hace competitivo en cualquier lado. Y para Butigieg si queda con los dos dígitos no tanto pero mejora unas encuestas que creo que le infravalorar. A sensu contrario veo a Bloomberg, no me creo que tenga un 14 por ciento en las bases demócratas y menos con Klobuchar y Buttigieg tan fuertes. Pero puedo equivocarme. Biden no puede fallar. Necesita uno o dos podios estos días o llegará al supermartes más tocado que el cráneo de Rocky Balboa.

ResponderEliminarEran candidatos testimoniales en este momento. Así que impacto cero su retirada. Nevada es un caucus y en los caucus ganan los candidatos mejor organziados, en este caso Bernie y Buttigieg (y Biden y Warren si llegaran en mejor momento, pero no es el caso). A favor de Bernie juega que se supone que Buttigieg tiene problemas con las minorías y los sindicatos, y el electorado demócrata de Nevada se basa mucho en esas dos cosas. Creo que a Buttigieg puede pasarle lo de Romney en 2008, muchos buenos segundos puestos. Biden depende enteramente de Carolina del Sur, y más en concreto del voto negro. Allí veremos también qué gradod e penetración tienen Bernie, Buttigieg y Klobuchar en el voto negro. Hablamos del negro mayoritario, y de un estado con una historia particular con un impacto particular en el voto negro, que no es igual al negro muy minoritario de un estado muy blanco de Nueva Inglaterra. Es un tipo de negro, sobre todo el de cierta edad, que además es de una mentalidad tradicional en ciertas cuestiones socioculturales, por lo que la homosexualidad de Buttigieg podría ser un hándicap.

ResponderEliminarNo he mirado encuenstas. El 14 por ciento de Bloomberg me sorprende. Pero si es a nivel nacional creo que tiene poca trascendencia si encadena fracasos estado tras estado. El estado que puede irle mejor a Bloomberg es Florida, pero para entonces...

Sí...para entonces te puede caer un castañazo como el de Guiliani en 2008, que por esperar hasta Florida se quedó sin espacio ni tiempo para defender su candidatura. Curioso...los dos últimos ex alcaldes neoyorquinos.

ResponderEliminarY ya le están recordando las cosas que dijo en el pasado sobre grupos de intereses especiales demócratas. Es inviable como candidato demócrata.

ResponderEliminar